Compiler Design Course Experience @ CMU

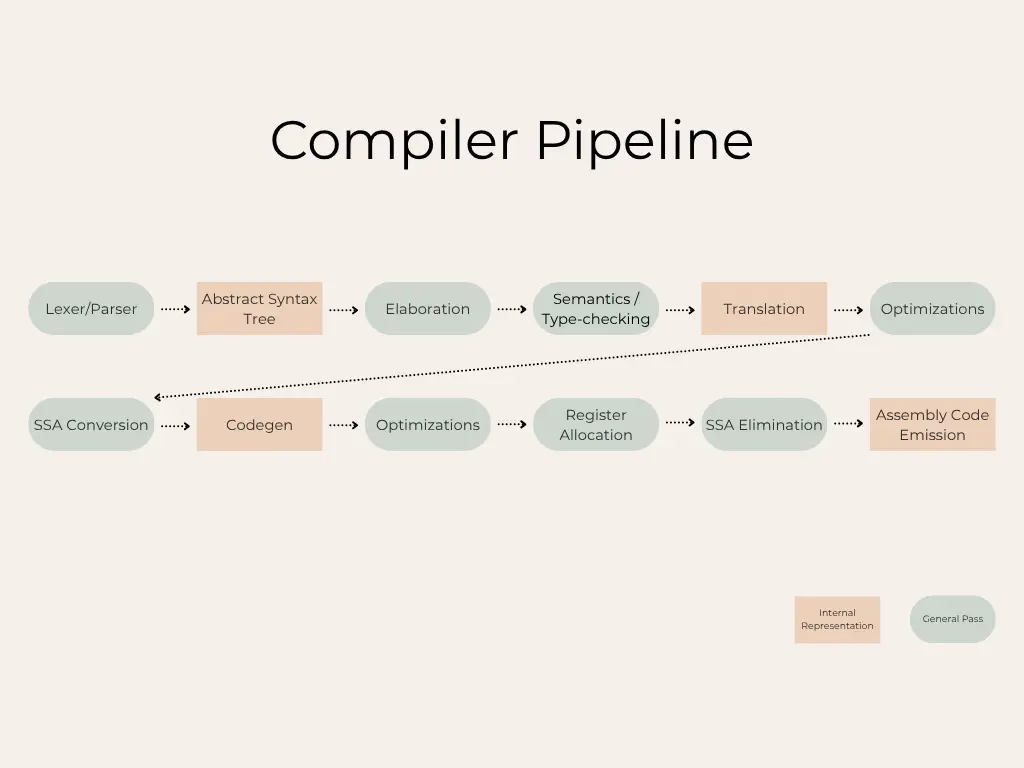

This is a reflection on my experience with the Compiler Design course (15-411) at CMU. It covers general course thoughts, what I enjoyed the most, and my personal takeaways. For context, 15-411 covers the design and implementation of compiler and runtime systems for high-level languages. Topics include lexical and syntactic analysis, type-checking, program analysis, code generation and optimization, memory management, and runtime organization. The course focuses on developing an end-to-end compiler pipeline for C0 (CMU’s memory-safe C subset).

Course Logistics/Structure

The course assignments are broken down into two categories: writtens and the actual compiler. I won’t go into too much detail because the writtens are not very interesting though still important; they can be summarized as being refreshers for topics such as dynamic/static semantics, grammar, and parsing. So, examples of problems you might see are things like using inference rules to verify that a statement typechecks or showing that a grammar is ambiguous.

As for the actual compiler portion, the project is done in teams of two. Students can use any language they prefer, though most choose OCaml or Rust (apparently some succeeded with Python). Additionally, the work is divided into five parts, each of which we refer to as a “lab.” Note that the approach taken can vary between semesters; in fact, during the semester I took the class, the course structure underwent major reforms. Specifically, the timeline was changed from six labs to five. This change enforced SSA in part of the compiler pipeline before the code review after Lab 3 and placed a heavier emphasis on optimizations. What had been removed from this new iteration of the course was an additional lab that required adding a feature, such as polymorphism, to the compiler. The content of this semester’s labs is as follows:

-

Lab 1: Students implement a compiler for a language that only supports arithmetic operations.

-

Lab 2: Students include support for boolean expressions, conditional statements/expressions, and loops.

-

Lab 3: Students need to add support for header files, typedefs, function declarations, and function definitions. Previously, only the main function was defined.

-

Lab 4: Students must implement a compiler that supports allocating and freeing memory in the heap. Specifically, there must be support for allocating and dereferencing structs (that is, their fields), arrays, and pointers.

-

Lab 5: This is the optimization lab where students are graded on how well their compiler performs relative to GCC -O1 on a benchmark suite (full points means matching GCC -O1’s performance). People generally enjoyed this lab the most, since by then students already had a working compiler (which my team found most annoying). This lab also requires students to write a detailed report on the effectiveness of their optimizations.

The code review mentioned previously is a graded assignment where students must work on proper documentation and ensure their compiler follows good coding style practices. After the submission period ends, students have the opportunity to review their code in detail with TAs. They can discuss anything from design choices to writing more effective code. I found this component of the course incredibly helpful as a developer.

Some Interesting Points

In this section, we’ll talk a bit about a few topics I found interesting.

Terminology

Before we get started, let’s quickly go over some relevant terms.

- Expression: a combination of operands and operators that can be evaluated to a value

- Statement: a unit that represents a single action in a program (yes, this is a bit abstract I know but think things that affect program state like

return 1andint x = 2) - Program: a sequence of statements

Elaboration

An elaboration pass is a separate pass on the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) to reduce redundant logic. What do I mean by reducing redundant logic? Consider a simple for loop:

1

2

3

for (int i = 0; i < 15411; i++) {

foo();

}

Equivalently, this can be defined as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

{

int i = 0;

while (i < 15411) {

foo();

i++;

}

}

Note that it is important to retain the scope of i for semantic purposes. So, for loops end up boiling down to being glorified while loops! We can do similar things with unary operators, as well as elaborate logical operators && and || into ternary operators. Nifty right? So, by reducing the number of available operators, we also reduce the number of subsequent logics we must account for. That said, one must be cautious when elaborating on certain operators. Otherwise, semantic information may be lost/altered, or an optimization opportunity may no longer be possible.

Typechecking

Typechecking in a statically-typed language like C0 can be done by recursively traversing the AST and ensuring that each construct satisfies the language’s typing rules. Viewed mathematically, this is the same as chaining a sequence of inference rules to derive the conclusion that an expression or statement is well-typed. OCaml’s algebraic data types and pattern-matching map directly onto AST variants and their typing rules, making it a natural fit. For example, say we have the following OCaml data type:

1

2

3

type expr =

| Binop of { lhs: expr; op: binop; rhs: expr }

| ...

Then, we can typecheck the Binop node by making recursive calls to retrieve the types of lhs and rhs (while verifying that they are well-typed) before checking that the retrieved types are compatible with op.

Of course, we will note that scope and other semantic details are relevant and can be kept track of by including an environment state parameter in the typechecking recursion logic. So, our logic would be something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let rec typecheck_expr env expr : expr_type =

match expr with

| Binop {lhs; op; rhs} ->

let t1 = typecheck_expr env lhs in

let t2 = typecheck_expr env rhs in

if compatible op t1 t2 then result_type op else error ...

| ...

Dangling Else

What is the dangling else (problem)? Consider the following statement:

1

if (outer_cond) if (nested_cond) nested_stm; else (outer_stm);

It could be parsed as either:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

if (outer_cond)

{

if (nested_cond)

nested_stm;

else

outer_stm;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

if (outer_cond)

{

if (nested_cond)

nested_stm;

}

else

outer_stm;

Notice that it is ambiguous how the nested conditional statements are interpreted. This is a problem concerning parser generators when the language allows for an optional else clause in an if-then(-else) statement. In languages like C, the dangling else is dealt with by always pairing each else with the nearest unmatched if. A way to enforce this in your grammar is to distinguish open statements (those lacking a matched else) from closed statements (those with a matched else). I’ll link the original paper and a wikipedia article if you want to read up on the specifics.

Lexer Hack

1

A * B;

In a compiler, the lexer first scans the source code to produce a stream of tokens. The parser then analyzes that token stream, matching it against grammar rules that define language constructs. Sometimes, however, a single sequence of tokens can satisfy more than one rule. In C, for example, the snippet above can be parsed either as a multiplication expression or as a declaration of B as a pointer to type A.

This ambiguity stems from the fact that the lexer does not distinguish between ordinary identifiers and typedef names. This is known as the “typedef-name: identifier” problem. A common solution is to report back to the symbol table during lexing. When the lexer encounters an identifier, it checks whether that name has been declared as a type and produces a different token accordingly. While this resolves the ambiguity, it is called a hack because it breaks the separation between the lexing and parsing stages.

Optimizations

Now, we’ll go a bit into some of the simpler optimizations that my partner and I implemented to provide a feel for what kind of techniques exist.

Tail Call Optimization

Many of my classes talked a lot about making recursive function tail calls. I didn’t really understand the importance until having to implement it myself. If you are not aware what tail call functions are, consider the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

int fact(int n){

if (n <= 1) {

return 1;

}

return n * fact(n-1);

}

int fact_tail(int n, int acc){

if (n <= 1) {

return acc;

}

return fact_tail(n - 1, n * acc);

}

Observe that we have written a factorial function twice, granted the second must be called slightly differently for equivalent results. Informally, a function is considered a tail call if it directly returns the result of a recursive call to itself. Therefore, it should be clear why the first is not a tail call.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

int fact_tail(int n, int acc){

base_case:

if (n <= 1) {

return acc;

}

acc = n * acc;

n = n - 1;

goto base_case;

}

Tail call recursive functions can easily be converted into a non-recursive function using goto instructions. This transformation eliminates all function-call overhead (no more pushing return addresses or arguments onto the stack) and prevents stack overflow for deep recursions.

With a bit of extra work, even functions that aren’t originally written in tail call form can often be refactored into a tail call equivalent form. fact is a classic example.

Inlining

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

return add(1, 2);

}

Function inlining is a very simple optimization. As hinted by its name, it essentially involves unrolling a function whenever the function gets called. With the above example, if we inline add, then we now have

1

2

3

int main() {

return 1 + 2;

}

You might be wondering, does this actually do anything? Well, for starters, it eliminates function-call overhead. Besides that, a recurring theme about optimizations is that they often improve the effectiveness of each other. By inlining, you expose formerly hidden expressions to passes like constant propagation, constant folding, and common subexpression elimination across what used to be function boundaries. Taking a look above again, we can see that inlining add enables 1 + 2 to be constant folded into 3!

But should you inline every function? Absolutely not. Inlining tends to increase code size, which can hurt instruction-cache locality and other hardware-related details. It also merges the callee’s locals and temporaries into the caller’s scope, lengthening live ranges and enlarging basic blocks. The result is higher register pressure which can lead to spilling registers onto the stack. When registers spill onto the stack, these loads and stores can reduce the very speed gains you hoped to increase.

Therefore, using this optimization effectively ultimately boils down to having a good heuristic on what functions to inline. Some things to consider are being recursive, the number of instructions, and the number of times the function is called.

Common Subexpression Elimination

1

2

3

4

5

6

int compute(int a, int b, int c) {

int t1 = a * b;

int t2 = a * b + c;

int t3 = (a * b) * 2;

return t1 + t2 + t3;

}

Observe that a * b is recomputed multiple times. This is unnecessary and can instead rewritten as:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int compute(int a, int b, int c) {

int prod = a * b;

int t1 = prod;

int t2 = prod + c;

int t3 = prod * 2;

return t1 + t2 + t3;

}

Simple enough, right? Common subexpression elimination works by looking for instances where the same expression (with the same operands) is computed multiple times and replaces the redundant computations with a single, shared value.

Important Note on Optimizations

Although many optimizations are intuitive, applying them safely in a real compiler requires detailed analyses to determine when they’re valid. In practice, each optimization is backed by its own analysis pass.

Course Thoughts

This course had been such a rollercoaster. I won’t lie, after implementing SSA completely broke our submission before the deadline of Lab 2, I was debating whether or not to drop the course. It all worked out in the end still, since it turned out we weren’t the only group that had a fair share of troubles. There ended up being a somewhat generous curve that brought our grades to an A.

One thing I thought was a really creative and surprisingly fun part of the course was the fact that all test cases are student-submitted. This meant that there were inevitably quite a few groups who tried their hardest to break other groups’ compilers. My friends and I would exchange war stories about whose compiler survived [Group] Bob Parr’s timeouts…

I probably would have enjoyed the class a lot more if we didn’t have such an incident in the first half of the class. The content was hard but rewarding, and the TAs were incredibly open to providing valuable insight. Not only were the instructors passionate and engaging in their lectures, but they also went the extra mile by providing breakfast at every session. We even got to learn more about future careers in compilers from talks by Apple and Jane Street representatives.

Personal Takeaways

Plan Thoroughly

I can’t overstate how much early design decisions came back to haunt me. Representing registers as plain strings, for example, was a major headache: string functions are troublesome to work with, and a single typo or capitalization mismatch could introduce subtle, hard-to-detect bugs. A far better approach would have been to define a dedicated register datatype or variant, enabling the OCaml type system to enforce correctness and simplifying pattern matches.

In general, I see now effective planning isn’t just about choosing an option that works today; it’s about anticipating the compounding effects of that choice and guarding against future pitfalls. I suppose I have to thank this class’s open-ended nature for teaching me this.

Be Modular

I underestimated how often I’d need to share the same graph structures and utility functions across multiple files. In hindsight, I should have made those components generic from day one. Instead, I spent a significant amount of time re-writing nearly identical classes and helper routines. Even when I did attempt more modular designs, I often ended up with glue code just to translate between slightly different type definitions, which defeated the purpose of reuse.

On top of that, it was my first exposure to OCaml’s type system, so I wasn’t aware that you can reference types from one module to another. As a result, I wrote a lot of icky conversion functions to bridge semantically equivalent types. Working with function parameters that varied by a few type constructors became incredibly frustrating.

Looking back, these patterns left our codebase overly fragmented and bloated. This has honestly given me first-hand experience of the importance of modularity.

Write Maintainable Code

To be quite frank, our codebase was somewhat of a mess to work with. Sparse documentation meant we often spent significant time deciphering each other’s code and sometimes even our own. Furthermore, as noted in Plan Thoroughly, certain implementations that worked initially quickly became inflexible when it came time to extend functionality. For instance, overusing wildcards in pattern matches caused us to miss unhandled cases. In hopes of minimizing my encounters with these terrible experiences again, I strive now, more than ever, to write code that is easy to build on top of.

Better Testing

I don’t have too much to say about this section, but creating scripts early on to test different parts of the compiler would have been incredibly beneficial for identifying what stage of the pipeline went wrong. Instead, we really only had automated tests for the final outputs.

Concluding Thoughts

I cannot begin to describe how much this course has taught me, not only in targetted course content, but important practices as a developer that I plan to keep close by. If you have any interest in systems, definitely take this course. If you don’t have that much of an opinion on systems, but have some time to spare, also take this course. I was in the latter category and still found the content incredibly interesting. While I might not go into specializing/working in compilers, knowing how these things work under the hood will definitely be beneficial long-term in writing more performant code.

Related Posts: